The Official Mort Künstler Website

My Friend, the Enemy - limited edition print

My Friend, the Enemy - limited edition print

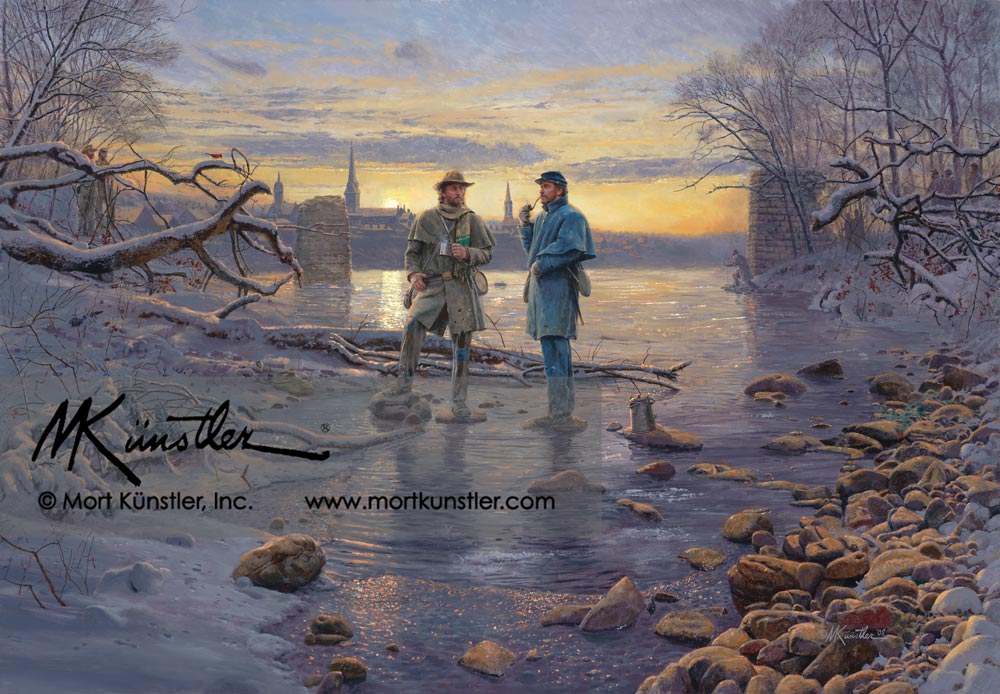

Rappahannock River, Va., December 25, 1862

Regular price

$300.00 USD

Regular price

Sale price

$300.00 USD

Unit price

per

Shipping calculated at checkout.

Couldn't load pickup availability

Custom framing is available for this print. Please call 800-850-1776 or email info@mortkunstler.com for more information.

LIMITED EDITION PRINTS

Paper Prints

Reproduction technique: Fine offset lithography on neutral pH archival quality paper using the finest fade-resistant inks.

Each print is numbered and signed by the artist and accompanied by a Certificate of Authenticity.

Image Size: 18” x 26” • Overall Size: 23” x 30”

Signed & Numbered • Edition Size: 350

Signed Artist’s Proof • Edition Size: 50

Fredericksburg Edition, Signed & Numbered • Edition Size: 100

Fredericksburg Edition, Artist’s Proof • Edition Size: 10

Giclée Canvas Prints

Reproduction technique: Giclées are printed with the finest archival pigmented inks on canvas.

Each print is numbered and signed by the artist and accompanied by a Certificate of Authenticity.

Signature Edition 17” x 24”

Signed & Numbered • Edition Size: 50

Signed Artist’s Proof • Edition Size: 10

Classic Edition 22” x 32”

Signed & Numbered • Edition Size: 50

Signed Artist’s Proof • Edition Size: 10

Historical Information

“We talked the matter over and could have settled the war in thirty minutes had it been left to us.” So said a Southern solider after he and a Northern counterpart sat on a log between the lines and enjoyed an unauthorized but friendly chat. As Americans, Johnny Reb and Billy Yank had far more in common than typical combatants. That familiarity was frequently revealed in friendly contact between the lines. Countless episodes of enemy soldiers helping each other occurred during the war. During the battle of Kennesaw Mountain in 1864, a ground fire threatened wounded Northern soldiers lying between the lines – until a Confederate officer stood up, exposing himself to enemy fire, and shouted, “We won’t fire a gun until you get them away.” An impromptu cease-fire followed immediately while Federal troops removed their wounded – then the battle resumed.

Following the battle of Second Manassas, two Confederate soldiers were carrying a wounded friend through the darkness when they were challenged by a sentry who demanded identification. “We are two men of the Twelfth Georgia, carrying a wounded comrade to the hospital,” they shouted back, only to learn they had accidentally crossed into Federal lines. “Go to your right,” the Northern sentry called out, directing the men back toward the Southern lines. “Man, you’ve got a heart in you,” hollered one of the retreating Southerners.

When the opposing lines were close enough, and the shooting had temporarily stopped, army musicians sometimes engaged in battles of the bands. On the banks of the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, Virginia, Southern soldiers listened admiringly to a Northern band performance during the winter of 1862. When it concluded, a Johnny Reb called out, “Now give us some of ours” – and the Yankee band obliged with a rendition of “Dixie.” When the band concluded, soldiers from both sides broke into a melancholy chorus of “Home, Sweet Home.”

The lines were so close on the Rappahannock during the winter of 1862-3, that contact between Northern and Southern soldiers became commonplace. They often met on an island in the river, where Confederate troops exchanged Southern tobacco for the coffee ration issued to Northern soldiers. When officers discouraged contact, they would make their exchanges by small, hand-made boats that the soldiers called “fairy fleets.” Sometimes they met to play cards; other times they just exchanged stories. The war was the real enemy, they concluded, and not each other – and if they had to go back to shooting at each other the next day, it wasn’t personal for many of them. For most, the camaraderie became genuine reconciliation at war’s end, and when Johnny Reb and Billy Yank chanced to meet after the war, it was often with obvious friendship and mutual respect. “My friend, the enemy,” veterans of the war came to call each other – with the understanding that, Northern or Southern, they were Americans all.

Mort Künstler’s Comments

I always look for subjects to paint that have never been done. With snow scenes, I always try to develop a different color scheme. Both goals are difficult to achieve, but I believe it has happened with “My Friend, the Enemy.” The location and the time of day enabled me to paint a different color scheme – and no modern artist of note has painted a scene quite like this one.

“My Friend, the Enemy” is set on Virginia’s Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg following the terribly bloody battle that occurred there a few weeks earlier. As if they were weary of the war’s inhumanity, Southern and Northern soldiers began meeting with each other between the lines. Such fraternization was forbidden on both sides, but the soldiers did so anyway that winter. They met to play cards, exchange gossip and barter Northern coffee for Southern tobacco. The painting is set on the side of the river occupied by General Ambrose Burnside’s Army of the Potomac. A handful of Confederate soldiers from General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia have made their way across the river to trade with the Northern troops. The soldiers are cautious, but trusting – and in the background other soldiers are making exchanges with a rigged-up, hollow log that serves as a ferry for their bartered items.

It’s the unique, peaceful and colorful kind of subject that I enjoy painting. It’s based on careful research, of course, but to me its appeal is the historical fact that makes the Civil War so fascinating and compelling – the human element. This terrible conflict was really a grand-sized family feud. Like these soldiers, most Americans North and South held nothing personal against each other – they were all Americans caught up in an awful war. That’s how the nation was restored when the fighting ended: Despite the horrendous losses, the best people on both sides had always viewed their counterpart in blue or gray as “My friend, the enemy.” That reconciliation, hinted at in this painting, is the great and wonderful story of the American Civil War.

View full details

LIMITED EDITION PRINTS

Paper Prints

Reproduction technique: Fine offset lithography on neutral pH archival quality paper using the finest fade-resistant inks.

Each print is numbered and signed by the artist and accompanied by a Certificate of Authenticity.

Image Size: 18” x 26” • Overall Size: 23” x 30”

Signed & Numbered • Edition Size: 350

Signed Artist’s Proof • Edition Size: 50

Fredericksburg Edition, Signed & Numbered • Edition Size: 100

Fredericksburg Edition, Artist’s Proof • Edition Size: 10

Giclée Canvas Prints

Reproduction technique: Giclées are printed with the finest archival pigmented inks on canvas.

Each print is numbered and signed by the artist and accompanied by a Certificate of Authenticity.

Signature Edition 17” x 24”

Signed & Numbered • Edition Size: 50

Signed Artist’s Proof • Edition Size: 10

Classic Edition 22” x 32”

Signed & Numbered • Edition Size: 50

Signed Artist’s Proof • Edition Size: 10

Historical Information

“We talked the matter over and could have settled the war in thirty minutes had it been left to us.” So said a Southern solider after he and a Northern counterpart sat on a log between the lines and enjoyed an unauthorized but friendly chat. As Americans, Johnny Reb and Billy Yank had far more in common than typical combatants. That familiarity was frequently revealed in friendly contact between the lines. Countless episodes of enemy soldiers helping each other occurred during the war. During the battle of Kennesaw Mountain in 1864, a ground fire threatened wounded Northern soldiers lying between the lines – until a Confederate officer stood up, exposing himself to enemy fire, and shouted, “We won’t fire a gun until you get them away.” An impromptu cease-fire followed immediately while Federal troops removed their wounded – then the battle resumed.

Following the battle of Second Manassas, two Confederate soldiers were carrying a wounded friend through the darkness when they were challenged by a sentry who demanded identification. “We are two men of the Twelfth Georgia, carrying a wounded comrade to the hospital,” they shouted back, only to learn they had accidentally crossed into Federal lines. “Go to your right,” the Northern sentry called out, directing the men back toward the Southern lines. “Man, you’ve got a heart in you,” hollered one of the retreating Southerners.

When the opposing lines were close enough, and the shooting had temporarily stopped, army musicians sometimes engaged in battles of the bands. On the banks of the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, Virginia, Southern soldiers listened admiringly to a Northern band performance during the winter of 1862. When it concluded, a Johnny Reb called out, “Now give us some of ours” – and the Yankee band obliged with a rendition of “Dixie.” When the band concluded, soldiers from both sides broke into a melancholy chorus of “Home, Sweet Home.”

The lines were so close on the Rappahannock during the winter of 1862-3, that contact between Northern and Southern soldiers became commonplace. They often met on an island in the river, where Confederate troops exchanged Southern tobacco for the coffee ration issued to Northern soldiers. When officers discouraged contact, they would make their exchanges by small, hand-made boats that the soldiers called “fairy fleets.” Sometimes they met to play cards; other times they just exchanged stories. The war was the real enemy, they concluded, and not each other – and if they had to go back to shooting at each other the next day, it wasn’t personal for many of them. For most, the camaraderie became genuine reconciliation at war’s end, and when Johnny Reb and Billy Yank chanced to meet after the war, it was often with obvious friendship and mutual respect. “My friend, the enemy,” veterans of the war came to call each other – with the understanding that, Northern or Southern, they were Americans all.

Mort Künstler’s Comments

I always look for subjects to paint that have never been done. With snow scenes, I always try to develop a different color scheme. Both goals are difficult to achieve, but I believe it has happened with “My Friend, the Enemy.” The location and the time of day enabled me to paint a different color scheme – and no modern artist of note has painted a scene quite like this one.

“My Friend, the Enemy” is set on Virginia’s Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg following the terribly bloody battle that occurred there a few weeks earlier. As if they were weary of the war’s inhumanity, Southern and Northern soldiers began meeting with each other between the lines. Such fraternization was forbidden on both sides, but the soldiers did so anyway that winter. They met to play cards, exchange gossip and barter Northern coffee for Southern tobacco. The painting is set on the side of the river occupied by General Ambrose Burnside’s Army of the Potomac. A handful of Confederate soldiers from General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia have made their way across the river to trade with the Northern troops. The soldiers are cautious, but trusting – and in the background other soldiers are making exchanges with a rigged-up, hollow log that serves as a ferry for their bartered items.

It’s the unique, peaceful and colorful kind of subject that I enjoy painting. It’s based on careful research, of course, but to me its appeal is the historical fact that makes the Civil War so fascinating and compelling – the human element. This terrible conflict was really a grand-sized family feud. Like these soldiers, most Americans North and South held nothing personal against each other – they were all Americans caught up in an awful war. That’s how the nation was restored when the fighting ended: Despite the horrendous losses, the best people on both sides had always viewed their counterpart in blue or gray as “My friend, the enemy.” That reconciliation, hinted at in this painting, is the great and wonderful story of the American Civil War.